Meet GREG

The Ground Effect Glider (GREG) was a ground effect model aircraft I and three other aerospace engineers from Stanford build and tested in 36 hours. This was part of the TreeHacks Hackathon hosted by Stanford each year. Our goal was to demonstrate efficiency improvements taking advantage of improved aerodynamic characteristics resulting from interactions with the ground.

Ground Effect Principles

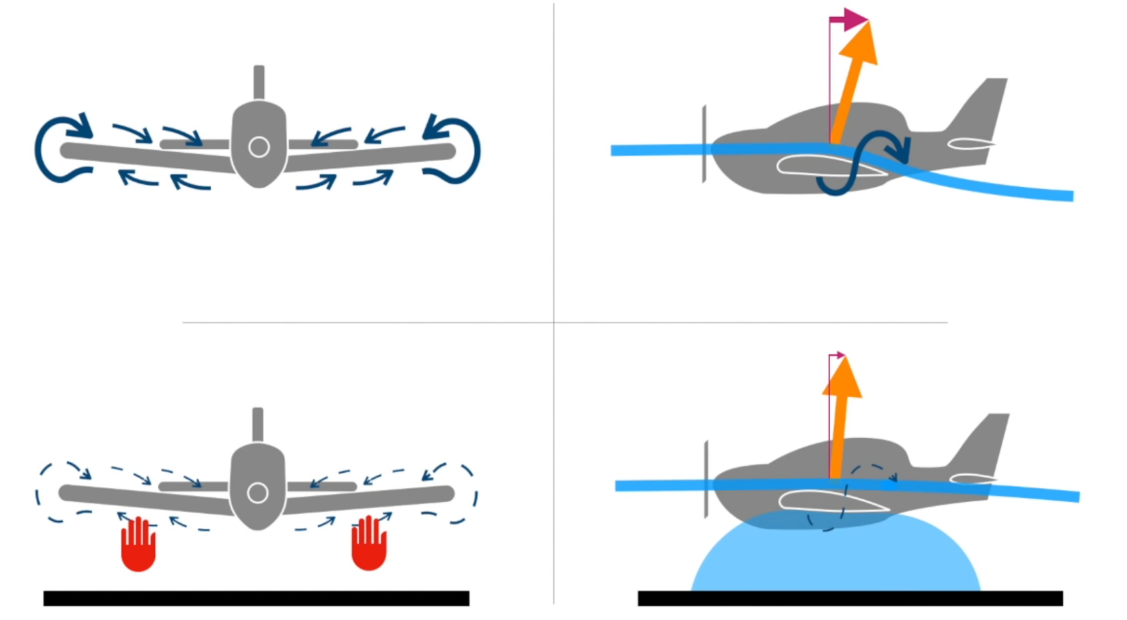

When flying near a ground surface (including water), the aerodynamic flow patterns of an aircraft change due to interactions with the ground in the vertical direction. This changes the wing upwash, downwash, and tip vortices. The sum total of these effects are generally referred to as the ground effect. A simplified demonstration can be seen below where the airflow of a normal aircraft is compared with that of one flying in the ground effect.

Note the apparent “cushion” of air underneath the aircraft. This is a bubble of high pressure air that is compressed between the ground and the bottom of the aircraft. Because of its presence, the aircraft is able to generate more lift.

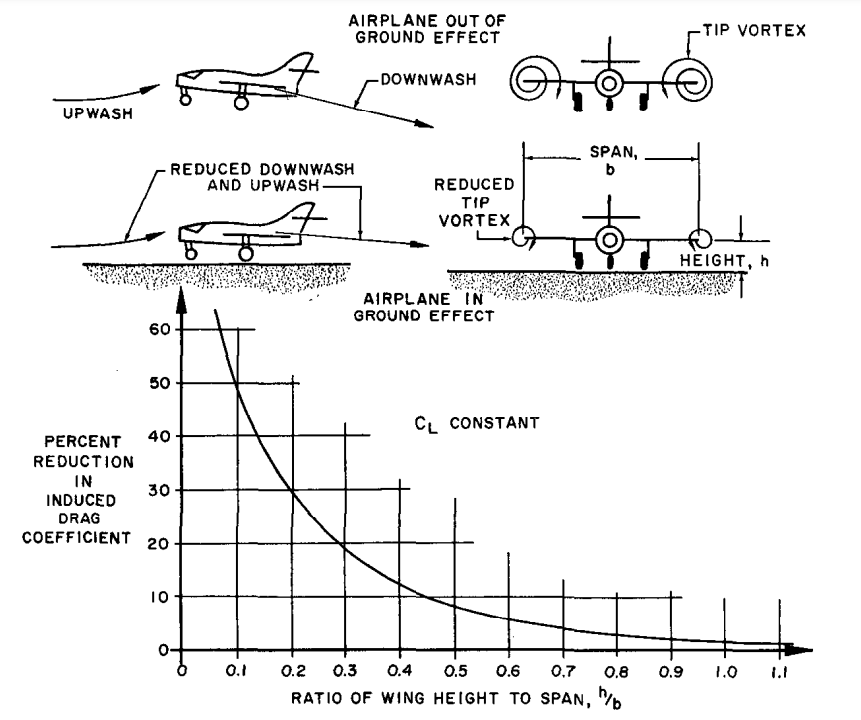

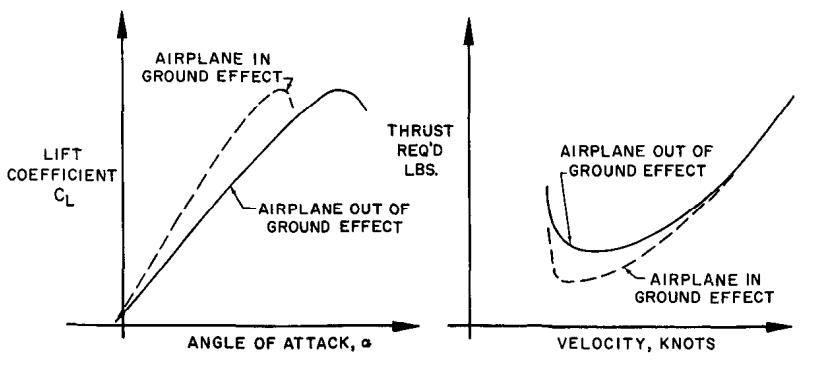

Another noteworthy effect is the reduction in the upwash and downwash, and therefore the wingtip vortices. The wingtip vortices deflect the airflow downwards thus creating induced drag (lift in the direction opposite to the aircraft’s forward motion). While operating in the ground effect, the wingtip vortices are restricted and the induced drag is therefore reduced. Another effect of the altered vortices is a reduction in the induced angle of attack. Practically, this means the aircraft requires a lower angle of attack to realize the same lift coefficient.

The figure above shows the benefits of the ground effect as a function of the height above the ground (in units of wing span). As can be noted, the closer an aircraft is to the ground, the larger the drag reduction.

Another important consideration is the angle of attack as seen above. As noted before, the ground effect allows for the same lift coefficient to be realized with a smaller angle of attack. Additionally, the thrust compared to velocity tells an interesting story. At higher speeds, parasitic drag dominates the drag forces on an aircraft. As such, the main benefit of the ground effect (a reduced induced drag) is created at lower speeds.

Useful Resources:

Ground Effect Vehicles

Ground effect vehicles (GEVs) are vehicles that are designed to operate in the ground effect regime, typically heights of less than half the wingspan off the ground. The father of such vehicles is generally considered to be the Soviet engineer Rostislav Alexeyev and the German engineer Alexander Lippisch.

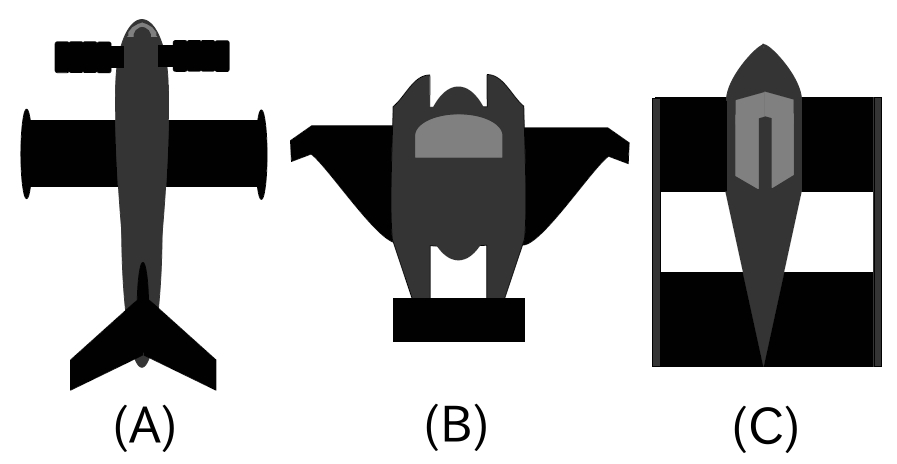

There are a few different wing configurations typically seen on GEVs:

-

(A) The straight wing configuration.

(B) The reverse-delta wing configuration.

(C) The tandem wings configuration.

The most popular today appears to be the reverse-delta configuration due to its excellent stability properties and apparent superior performance.

GEVs have a wide range of applications including cargo transit, military, and search and rescue amongst others. In these spaces, GEVs must compete against conventional aircraft as well as marine vehicles. With regards to marine craft, the typical maximum speed is approximately 100 km/h with high power requirement and fuel consumption. This is induced by the viscous drag of water friction. The largest GEV ever built is the Korabl’ Maket, otherwise known as the Caspian Sea Monster. It weighed approximately 500 tons and was capable of speeds up to 500 km/hr.

Compared to traditional airlines, it was suggested in a 1994 Advanced Projects report that GEVs were less efficient during cruise. It is unclear if this sentiment remains today. A popular concept being investigated now is electric GEVs, such as the one proposed by REGENT. Additionally, DARPA has launched the “Liberty-Lifter” program which aims to develop GEV based cargo transport vehicles.

There are quite a few benefits when considering GEVs:

- Lower operational costs when compared to traditional aircraft

- Safety benefits associated with flying so low

- Higher speeds, higher efficiency, better lift-to-weight ratio than competing marine craft

- Flies below radar profile, can easily avoid aquatic weapons such as torpedoes

- Low infrastructure costs, existing ports should suffice

- Higher comfort sea-travel

Useful Resources:

- Stability, Control and Performance for an Inverted Delta Wing-In-Ground Effect Aircraft

- Could the Airfish-8 finally get the Wing In Ground Effect Vehicle up and running?

- REGENT

- DARPA Liberty Lifter aims to bring back heavy-lift ground effect seaplanes

- Ekranoplans: Autonomously Expanding the Limits

- Ground effects utilizing and transition aircraft

The Build

Given we only had 36 hours to build GREG, we opted to use materials that were available and lightweight including

- Foamboard

- Carbon Fiber Rods

- Hot Glue

- Gorilla Tape

- Balsa Wood

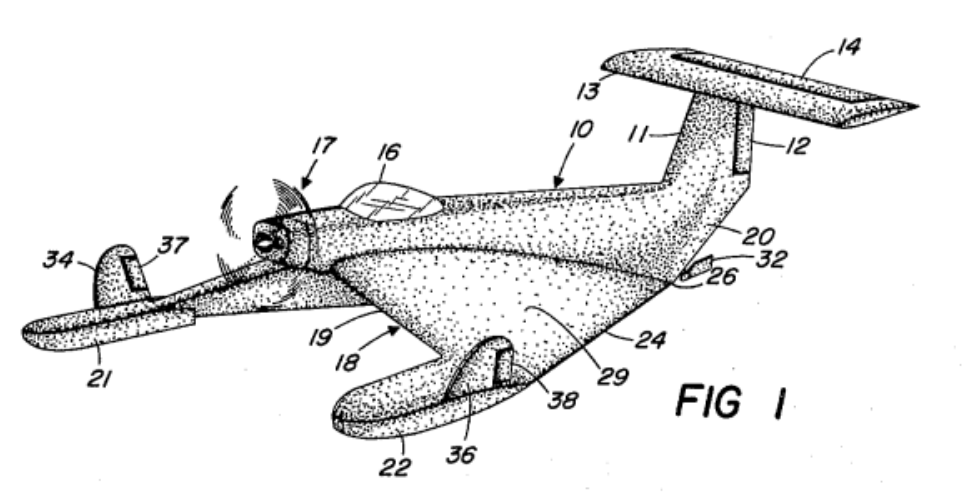

Flight controls were accomplished with a pilot manning a radio transmitter controller. A DC motor and propeller were used to provide thrust (propulsion calculations were accomplished with ecalc). Two rudders and one elevator controlled with micro-servos operated as the control surfaces for pitch and yaw. Two rudders were used to ensure we’d be able to turn the aircraft sufficiently.

The wing was designed to take advantage of the ground effect. The distinct downward slant on the wing was to bring the wing tips closer to the ground. The winglets on the sides counteract wind and other adverse aerodynamic forces. A large, tall tail keeps the backwash from the front wing from reducing the lift generated in the tail and creates a moment to counteract the pitching up of the aircraft. Finally, we created an airfoil shape on the foamboard wing by attaching a curved piece of balsa wood.